How our modern-day Santa Claus and his reindeer sleigh evolved from Norse myth

How our modern-day Santa Claus and his reindeer sleigh evolved from Norse myth

Judith Gabriel Vinje

Los Angeles

Santa Claus owes his very existence to the old Norse myths. He’s changed a lot over the centuries, but his origins in Scandinavia and Northern Europe cannot be denied.

Here’s a look at how Santa Claus emerged from the lands of the Vikings, exchanging the Norse god Odin’s more terrifying traits for those of a plump, chuckling man of eternally good nature.

Odin was chief among the Norse pagan deities. (We still remember him in the day of the week named for him, Wednesday, Woden’s Day.) He was spiritual, wise, and capricious. In centuries past, when the midwinter Yule celebration was in full swing, Odin was both a terrifying specter and an anxiously awaited gift-bringer, soaring through the skies on his flying eight-legged white horse, Sleipnir.

Back in the day of the Vikings, Yule was the time around the Winter Solstice on Dec. 21. Gods and ghosts went soaring above the rooftops on the Wild Ride, the dreaded Oskoreia. One of Odin’s many names was Jólnir (master of Yule). Astride Sleipnir, he led the flying Wild Hunt, accompanied by his sword-maiden Valkyries and a few other gods and assorted ghosts.

The motley gang would fly over the villages and countryside, terrifying any who happened to be out and about at night. But Odin would also deliver toys and candy. Children would fill their boots with straw for Sleipnir, and set them by the hearth. Odin would slip down chimneys and fire holes, leaving his gifts behind.

Centuries passed, and the world was changing. About the time paganism was being replaced by Christianity—which happened centuries later in the north than the rest of Europe—honoring Odin became forbidden. Yule was rescheduled to coincide with the Christian celebrations, and Odin was pushed out of the picture.

First the chief god was replaced by the goodly Christian Saint Nicholas, a fourth-century Greek bishop. Always depicted wearing a red cloak, he became known as the patron saint of giving in most parts of Europe—but not Scandinavia. He had helpers who would report on which children were good. He’d deliver gifts to the good kids. Beware the punishments dealt out to those who were bad!

After the Reformation, Nick and the other saints became forgotten in all the Protestant countries of Europe except Holland. There he morphed into Sinter Klaas, a kind and wise old man with a white beard, white dress, and red cloak. He’d ride the skies and roofs of the houses on his eight-legged white horse, delivering gifts through the chimney to the well-behaved children on his birthday, Dec. 6, St. Nicholas Day. Reminds you of Odin, right?

17th-century Dutch immigrants brought their tradition of Sinter Klaas to America, and his name changed into Santa Claus.

Santa Claus: a portly, jolly man with a white beard, wearing a red coat, carrying a bag full of gifts for children. This image became popular in the U.S. in the 19th century after the publication of the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” by Clement C. Moore. The eight-legged horse was replaced for eight flying reindeer. And of course, where do reindeer come from in the first place?

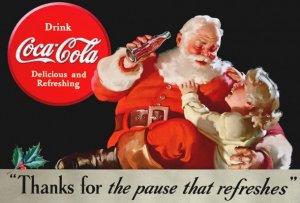

Santa’s image got more popular through advertisements for Coca-Cola in the 1930s. The artist, Haddon Sundblom, was the son of Finnish immigrants. Before Sundblom reinvented him, Santa had been a tall, wizardly looking fellow, much more like Odin. The Finns held on to a more ancient image of the Yule master for centuries. The Joulupukki or “Yule Buck” is originally a pagan tradition. He is connected to Odin and said to wear red leather pants and a fur trimmed red leather coat. But Sundblom also remembered the jovial Dutch Santa Claus with his red cloak and long white beard.

As for the elves in Santa’s North Pole workshop who work all year long making Christmas toys, it was Odin who was the lord of Alfheim, home of the elves. And all magical weapons and jewelry of the gods and goddesses were fashioned by highly skilled dwarves, who dwelled deep within the earth.

In steps the Yule goat, the giver of gifts until the 19th century. A popular theory is that the celebration of the goat is connected to worship of the Norse god Thor, who rode the sky in a chariot drawn by two goats. Today, the Yule goat in Scandinavia is best known as a Christmas ornament, made out of straw and bound with red ribbons.

In the 19th century, as American Santa Claus traditions were now spreading to Scandinavia, the Nordic julenisse started to deliver the Christmas presents, replacing the Yule Goat.

In Norway, it is said that the Julenisse or Santa Claus was born under a rock in Vindfangerbukta north of the town of Drøbak on the Oslofjord, several hundred years ago. Today, Drøbak is considered the premier Norwegian Christmas town, with its popular Christmas house or Julehuset located right next to the town hall. Busloads of people come to see the julenisse, trolls, elves, and gnomes in the house. Whether tourists know it or not, these are the image descendants of the one-eyed god Odin.

Folklore experts can’t deny the legacy of Odin, and his transformation into new versions of Yule gift-bringers. Margaret Baker, author of “Discovering Christmas Customs and Folklore” comments that “The appearance of Santa Claus or Father Christmas, whose day is the 25th of December, owes much to Odin, the old blue-hooded, cloaked, white-bearded Giftbringer of the north, who rode the midwinter sky on his eight-footed steed Sleipnir, visiting his people with gifts.”

These figures, preserved and evolved from myth and pagan belief and folkore, light up the imagination during the longest, darkest days of the year. For Christians, that light emanates from a babe in a manger in far-off Bethlehem, worlds away from the Norse gods, the elves, the goats, and the wild hunt. In Norway, when people greet each other with God Jul—Good Yule—that origin of the Christmas observance becomes the star of the season.